Reflections on Vancouver, British Columbia and other topics, related or not

Quixote amid the terror

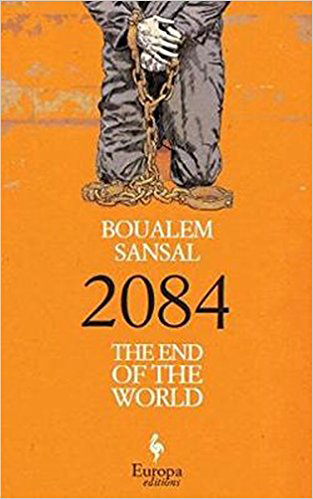

Vicious as it is, Boualem Sansal’s dystopia

offers a glimmer of hope not seen in Orwell’s work

Greg Klein | September 17, 2017

This is the world. Abistan took over where Ingsoc left off, having conquered Winston Smith’s former home and recognized how Big Brother’s methods of mass manipulation could complement a religion perverted into a viciously absolutist regime.

This is the world. There is no past, just the totalitarian present. No other countries or societies either, notwithstanding rumours—absurd, heretical flights of fancy—not only of foreign populations living in segregated ghettos but a border. A mythical, legendary, blasphemous border to somewhere or something else, maybe a gateway to another country or a doors-of-perception metaphor. Or both.

This is the world. Citizens revel in mass public executions, the holy word transforms wastrels into suicidal jihadists and people live in constant fear that their frequent attestations of total submission to their demigod leader might be deemed inadequate. It’s in this world that two almost unbelievably naive individuals embark on a perilous quest, searching for a possible border to a world unlike their own.

Officially there is no world outside Abistan and in practice none can be imagined, due to the way their Newspeak-like lingo restricts thought. But a combination of circumstances gives Ati and Koa an inchoate idea that maybe there is something other than this world, where it seems that “life had died long ago, and that people were so damaged by their uselessness that they were just vague traces of life, painful memories wandering in a lost time.”

They encounter another freethinker, one far more advanced. He’s already crossed a border of sorts, having overcome the barrier to realizing there was a world before Abistan’s birth in 2084. He manages to study its last few centuries, seeing “madness, unrestrained freedom, insurmountable danger, already, but there were also innumerable, serious sources of hope...”

He also watched “as 2084 arrived and was followed by the Holy Wars and the nuclear holocausts; more importantly, he witnessed the birth of the absolute weapon which one does not need to buy or build, the conflagration of entire populations as they are filled with the violence of terror.” He wishes he could have warned them of what was coming, a warning that Sansal offers to the present from his imaginary future.

Sansal, whose work gets censored in his native Algeria, obviously based this satire on Islam. But before Canada’s anti-Islamophobia zealots follow his country’s example, they might consider this passage that describes:

... an ancient religion which had once brought honor and happiness to many great tribes of the deserts and plains; but its inner workings had been broken by the violent, discordant use that had been made of it over the centuries, and this had been aggravated by the absence of competent repairmen or attentive guides.

Might that in any way offer a parallel to liberalism?