Reflections on Vancouver, British Columbia and other topics, related or not

Fraser River rush revisited

New research shows how gold fever

brought American warfare north of the border

Greg Klein | August 3, 2018

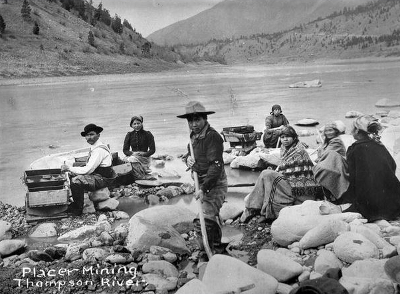

Natives mined and traded gold for about

two years prior to being overrun by newcomers.

(Photo: Royal British Columbia Museum)

Is this the price of gold—the murder of defenceless people followed by retaliatory beheadings as a private American army threatens genocidal war in the future Canada? There’s more to British Columbia’s first great gold rush than has been acknowledged and, 160 years after the fact, a newly published book casts harsh light on the Fraser River mania and its accompanying Fraser River War.

That the war even happened will take many people by surprise. Downplayed or ignored in Canadian research, its significance gets special emphasis in Claiming the Land: British Columbia and the Making of a New El Dorado. The war constitutes one of a number of surprises in what author Daniel Marshall, a University of Victoria professor and descendant of 1858 arrivals from Cornwall, calls a “substantial revisionist history.”

Officially, the rush began with the sudden arrival of some 450 “dregs” of the California goldfields, unloaded by steamboat in April 1858 at the Hudson’s Bay Company fort in Victoria. But HBC officials including chief factor and Vancouver Island colonial governor James Douglas had been anticipating such an event for two years, all the while buying gold from native placer miners. That ongoing trade, of course, belies stories of a dramatic discovery that sparked the rush.

Douglas even tried to discourage such an event by posting pre-rush ads in American newspapers asserting British authority over the mainland of present-day B.C. (then under HBC jurisdiction) and warning that the natives “are decidedly dangerous and that they have forcibly expelled all the whites who have attempted to work Gold in their country.” Hedging his bets, he also ordered the company to manufacture California-style mining gear that the HBC could flog to new arrivals via roving teams of travelling salesmen.

Natives had already fended off gold miners at the aborted Queen Charlottes rush of 1851, when they expelled an HBC crew and fought off American boats. Haida Gwaii aboriginals had devised a way of extracting sub-surface gold by heating rock with fire, then cooling the expanded rock with water to break it up. They reportedly made bullets of gold, an ironic choice of ammo to use on rival miners. But on the mainland, HBC traders worked amicably with native miners, who added yellow metal to the furs and salmon that they provided the company for export.

No stronger contrast could be imagined with circumstances south of the border. All-out war raged between the U.S. Army and massed tribes of eastern Washington territory. In one battle, 1,200 natives delivered a monumental defeat to their adversaries just as the rush was gaining momentum.

As for California’s ’49ers, some of them considered “Indian fighting” an integral part of gold mining. Between 1848 and 1870, an estimated 50,000 California natives died of disease, starvation or murder. When placer mining played out and news arrived of gold on the Fraser, “much of the cultural mentality that informed the genocidal attitudes of the California mining frontier was baggage carried north with the requisite pick, pan, and shovel.”

Among those joining the rush were Chinese veterans of California, Cornish and Welsh miners with experience in a number of camps, hundreds of blacks and some “violently” republican former French soldiers encouraged to emigrate by Paris police after their country’s 1848 revolution.

But, with British military presence ending at the Fraser’s mouth, it was the white Americans—sometimes egalitarian and racist at the same time—who proved the biggest threat to colonial authority and aboriginal security.

Among them were not only Indian fighters but filibusters, Americans who had joined privately organized militias in attempted conquests of foreign territory. Some targets included Sonora, Baja California, Cuba and Nicaragua, where in the latter case a short-lived filibuster regime gained official recognition from the U.S.

Dreams of American Manifest Destiny and loose talk of 54-40 or Fight extended in time and space past the international boundary set at the 49th Parallel in 1846. With at least 30,000 newcomers, maybe many more, pouring into the yet-to-be-proclaimed colony of B.C., Americans flouted the almost non-existent British authority to establish their own California-style laws and customs.

Miners who fought their way through the dangerous overland routes from Washington territory brought the Indian Wars with them, as they took revenge on defenceless targets north of the border.

“The old Californian miners and Indian-fighters were the worst, [believing that] they could travel in small parties and clean out all the Indians in the land.”

—A contemporary prospector

Both rumours and credible reports circulated of increasing harassment and shootings on both sides, with dozens dead and headless corpses floating downriver, nine past Fort Yale, another six at Union Bar and stories of many more. Thousands of natives were said to have united, pushing newcomers back to Yale, where hundreds of miners formed five mounted militias. “Some were for exterminating all Native peoples encountered,” Marshall writes, “while others offered to broker a peace settlement supported by a large demonstration of armed force.”

The latter sentiment prevailed, as Captain Henry Snyder of the 250-strong Pike Guards, supported by a French militia, overshadowed the much smaller Whatcom Guards, who advocated wholesale slaughter. Pushing north, Snyder’s group held a dramatic meeting with Spintlum, described as the war chief for the Fraser region. He convinced 10 other Nlaka’pamux chiefs to pursue peace. An American army, supported by a French army, and the massed aboriginal bands ended their war in the nominally British region.

Within Canadian historical study “it is usually assumed that there is no parallel incident in Canada to the kinds of Native-newcomer violence that occurred in the American mining West,” Marshall points out. “There was, however, a most notable and neglected exception.”