Reflections on Vancouver, British Columbia and other topics, related or not

Identity politics:

On the edge of self-destructing chaos?

Greg Klein | November 1, 2021

Despite an often fascinating perspective Niall Ferguson’s

insight eventually fails, almost suggesting a Pollyannish outlook.

What could be less surprising than a mainstream academic, a pop historian at that, who misunderstands the social revolution? Niall Ferguson’s pandemic-inspired book Doom: The Politics of Catastrophe looks at a range of disasters past, present and possibly future while downplaying the upheaval all around us. But he unwittingly reinforces an interesting perspective on the fragility of a multi-faceted coalition intent on destroying the West.

Before addressing that, however, it’s worth looking at the insights Ferguson does offer for the apocalyptically preoccupied. Whether catastrophes are biological, political, social, economic, geological, environmental or even inter-stellar, he maintains, “at some level all disasters are man-made.” Regardless of cause, humanity has a way of aggravating circumstances.

He writes about the Spanish flu that started in 1918, killing 40 to 50 million, more than WWI but less than the catastrophe of communism. After typhus killed up to three million in the Russian Civil War the victors unleashed two man-made famines on Ukraine, from 1921 to 1923 and 1932 to 1933. The latter spilled into Russia and especially Kazakhstan, killing about five million people altogether. “Stalin’s conception of class war implied not just terror but mass murder,” Ferguson states.

The agricultural disaster imposed by China’s Great Leap Forward from 1959 to 1961 killed between 30 and 60 million. Ethiopian communists caused their 1984-to-1985 famine, an atrocity overlooked by pop fans swooning over the Live Aid music fest.

Ferguson surveys epidemics from fifth-century BC Athens through the bubonic outbreaks to 20th century Asian flu, AIDS/HIV, SARS, MERS and Ebola, up to the current pandemic. China, he says, responded to Covid-19 as it did to SARS. The difference this time was the “acquiescence” of the World Health Organization, with the WHO’s China-backed Ethiopian director-general “supine, if not sycophantic.”

About seven million people left Wuhan in January 2020, Ferguson reports. When China finally restricted travel, the country imposed tighter controls on movement between Wuhan and the rest of China than between Wuhan and the rest of the world.

This planet’s history of disasters includes “an infinity of non-events” too, the author states. Only luck has (so far) prevented a meteor strike of existential proportions. Other possible threats might include an alien invasion (although the distances are incomprehensibly vast), solar activity, planet-swallowing black holes or an exponential expansion of the universe.

Humanity’s contribution to its demise might come from nuclear war, terrorism or accidents, biological weapons, cyber warfare, genetic engineering or nanotechnology that causes “some self-perpetuating and unstoppable process that drowns us in gloop.” Artificial intelligence can be used to enhance totalitarianism or justify its creation. Or AI could turn against us itself.

Ferguson notes AI theorist Eliezer Yudkowsky’s warning: Every 18 months, the minimum IQ necessary to destroy the world drops by one point. (Ferguson doesn’t provide the minimum starting point. Yudkowsky said that in 2008, nearly nine points ago.)

Ferguson completed this book before the vaccine controversies. Yet in discussing “science and the revival of magic,” he writes of “that vague deference to ‘the science,’ which proves, on close inspection, to be a new form of superstition.”

As for the obsession of Greta Thunberg, “the child saint of the twenty-first-century millennialist movement,” Ferguson says an eruption of Wyoming’s Yellowstone supervolcano “would render discussion of man-made climate change superfluous in the brief period before mass extinction ensued.”

Comparing the near-catastrophe of Cold War I with the potential catastrophe of Cold War II, he mentions that America’s allies of the first round prefer to remain non-aligned in the second. He points out that Western pop culture helped undermine Soviet power in version I, but he doesn’t acknowledge that it’s now undermining the West. Nor does he mention that, while the Soviets had Cold War spies, agents and sympathizers working abroad, as China does now, Beijing also has fifth columns across the West in CCP-loyal immigrant voting blocs.

As at least some of Ferguson’s previous 15 books indicate, he finds fascination in networks—social, political, economic, cultural, communications, infrastructure and so on. Each can be described as a complex system with many components held together only through a delicate equilibrium. The networks also intertwine into an even more complex entity.

Ferguson explains, “Some such systems operate somewhere between order and disorder—‘on the edge of chaos,’ in the phrase of the computer scientist Christopher Langton.”

Bernice Cohen’s 1997 book The Edge of Chaos: Financial Booms, Bubbles, Crashes and Chaos applies that perspective to a highly technical but often fascinating analysis of economic disasters dating back to the 1630s Dutch Tulip Mania. Ferguson points out how American subprime mortgages shattered the delicate equilibrium of global finance to crash the world economy in 2008. Lionel Shriver refers to complex systems in The Mandibles: A Family, 2029-2047, a 2016 novel that wonderfully expresses the human element of a financially induced societal collapse. (Ferguson’s survey of sci-fi and dystopian fiction ignores this American classic, yet he praises Margaret Atwood and the equally lame TV series Survivors.)

A very delicate equilibrium might be seen in the current social revolution. Certainly not a movement of reform, it proposes nothing remotely realistic to replace the society and culture it’s destroying. That will delight the many activists who simply hate normality. But they themselves could be threatened by ensuing chaos.

As a complex system, the social revolution shows what Ferguson would call phase transitions. Some examples include the 2016 election of Donald Trump, the 2017 Charlottesville confrontation, the 2020 George Floyd martyrdom and probably the 2021 Capitol Hill protest. Canada took these American events to heart and experienced an additional phase transition this year with sudden allegations that unmarked native graves that had long been publicly known indicate mass burials of atrocity victims. Each of these transitions brought a wildly disproportionate and seemingly irreversible escalation of activism, mainstream propaganda and sometimes official policy.

In addition to phase transitions, the revolution features a more fluid radicalization that continues through almost every aspect of Western society and culture. For example increasing levels of weirdness become mainstream with public celebrations of homosexuality, then homo marriage, homo adoption, sex change operations and now gender fluidity for children.

Could all this constitute an overly complex system doomed for self-destruction?

Montreal’s 2019 Pride Parade suggested future challenges to identity

equilibrium, when Chinese fascists harassed homo marchers.

(Photo: Free HK MTL)

The delicate equilibrium might face infighting. Some early indications came from blacks who delayed the 2016 Toronto Pride Parade and forced cancellation of its 2021 Boston counterpart, as well as the CCP-loyal Chinese who disrupted the 2019 Montreal Pride Parade. Of course those actions would be considered intolerable hate crimes were they not committed by privileged minorities—and supposed allies with homosexual culture in the war on the West.

The delicate equilibrium applies to institutions too. Schooling and academia have already collapsed under the Gleichschaltung of identity politics. Law enforcement and justice don’t have far to go. As medical care (staffed through affirmative action) prioritizes patients from a hierarchy of group identities, the spoils system should provoke greater resentment. And if education and employment denigrate merit, who’ll keep complex infrastructure running? “Traditional indigenous knowledge” somehow seems inadequate to provide nuclear power.

Comparisons can be made with some aspects of the French Revolution’s Great Terror, Nazi Germany, the USSR, the Maoist Cultural Revolution and other eras of madness. Vicious as they were, they lacked the complexity of today’s morass. A question for our time might be whether we endure a period of total chaos before a totalitarian regime imposes order, or whether we slide straight into totalitarianism.

Ferguson misses these possible scenarios, although he does mention some quasi-religious aspects of what he calls the “Great Awokening.” Examples include white cops washing the feet of black marchers, white BLM supporters displaying wounds, real or fake, of self-flagellation and whites kneeling on the pavement praying to blacks for forgiveness.

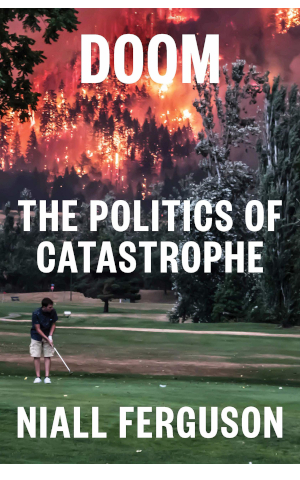

But in downplaying the extent of these manifestations Ferguson seems oblivious to our possible oblivion. The cover photo for one printing of his book shows a golfer intent on his game while a raging wildfire approaches. That image might serve as a metaphor for academics like Ferguson himself.

How’s my blogging?