Reflections on Vancouver, British Columbia and other topics, related or not

Decline and crash

Will the pandemic hasten

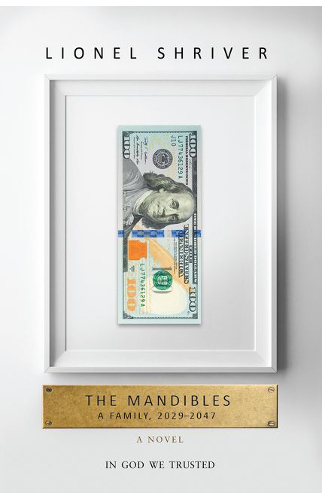

Lionel Shriver’s economic apocalypse?

Greg Klein | May 28, 2020

In a 2017 afterward, Shriver noted that the U.S. “is unlikely

to go down the tubes without taking the rest of the world

with it. The Mandibles is guilty of being too optimistic.”

“For months now, anchors had referenced the present with nouns like crisis, catastrophe, cataclysm, and calamity, and they were running out of C-words. They’d already used up the D’s, like disaster, debacle, and devastation. Terms like hardship, adversity, tragedy, tribulation, and suffering didn’t mean anything anymore—they didn’t work; they seemed to allude to experiences that were no big deal. The English language itself was afflicted by inflation, and when everything got ten times worse the newscasters would be stymied.”

Financial doomsayers have long predicted something like this. But probably no one has imagined it as clearly as Lionel Shriver, let alone examined its human side.

And if you think the apocalypse of the pandemic rules out the end times of the economy, you might find interesting Shriver’s comments in a current New Yorker profile. Or complexity theory as discussed in The Mandibles: A Family, 2029-2047. Released in 2016, Shriver’s novel presents a depressingly believable and gripping account of the not-distant future, a permanent, irreversible decline alien to the American psyche and to that of its northern neighbour. Canada’s barely mentioned, although its corresponding collapse is implied.

Shriver dramatizes a crisis beginning with an attack on American infrastructure that plunges the U.S. into barbarism. Government eventually imposes a degree of order and a severely straitened economy struggles to its feet. But even that’s shattered after China leads other countries in a reserve currency coup. The world finally rejects fiat American money.

For that to change, the eldest Mandible suggests, dollars would have to be backed by “a strictly proportioned basket of real commodities—corn, soy, oil, natural gas, deed to agricultural land. Rare earths… copper… Oh, fresh water sources! And gold, of course.”

The U.S. refuses. The country reneges on both foreign and domestic debt, bans the use of foreign currency and blocks the transfer of assets abroad. Businesses fail, unemployment soars, investments plunge, inflation runs wild, savings evaporate.

“ETFs, mining stocks, bullion on deposit—the Treasury neatly commandeered everything on the record in one fell swoop.”

Among the casualties are “economic survivalists” and their strategies: “ETFs, mining stocks, bullion on deposit—the Treasury neatly commandeered everything on the record in one fell swoop.” Wedding rings, too.

The middle class long since extinguished, American society turns into one huge underclass struggling for survival. Among the few signs of law are soldiers searching homes to confiscate gold.

This is no time for useless education and bullshit jobs. As realized by Willing, an adolescent who was only eight at the beginning of these tribulations, it’s an era calling for adaptation or death. Combining the most useful traits of various members of his mother’s family, he’s skeptical, insightful, eminently resourceful and loyal to family. There’s also something else, a quality harder to define that often has his mother Florence wondering about his fatherhood.

Her household, teeming with four generations of Mandibles, her Lat lover, an ex-tenant turned charity case and some disastrous in-laws, dramatizes how collapse affects character. It’s hard to define people and relationships by money and work when money and work almost cease to exist. In this story people define themselves by their response to circumstances.

“He was refining a skill, like purifying water and building a fire—one that would later come in handy when thou-shalt-not-steal joined anachronisms like lactose intolerance.”

Willing matures quickly as a new type created by adversity, reflecting a pioneering spirit largely unknown in this continent since the 1930s. As conditions get increasingly dangerous, desperate and weird, this unaffectionate but dutiful adolescent takes over from his mother as the mainstay of the family.

It’s not always an attractive transformation. He regards his growing criminality as “refining a skill, like purifying water and building a fire—one that would later come in handy when thou-shalt-not-steal joined anachronisms like lactose intolerance.”

Anyway, his moral degradation keeps him in sync with the growing corruption of American society. It’s something “like downloading the latest operating system.”

In stark contrast, there’s his uncle Lowell. Ineffectual and deluded, he hopes to revive his past life in a bullshit job—bullshit for its lack of not only usefulness but credibility. He’s an economist.

An unemployed economist, of course. “Economists are of very little economic utility,” his wife points out. “And he’s useless in every other regard too.”

Insisting that affluence will bounce right back and, most importantly, that he’s been right all along, he can’t even be mugged into reality. His exasperated wife chastises him for belabouring his Keynesian dissertations instead of helping their malnourished children comb the neighbourhood for junk that can be burned as fuel.

Crowded into cramped quarters, wearing dirty clothes, huddled under blankets for warmth, rationing food for its expense, saving water for its scarcity and fearing for their safety, this extended family typifies what’s left of the American middle class.

Government, when not entirely dysfunctional, acts as “a form of harassment.” But since the president and his administration come from Mexico, criticism equals racism. Mexico, meanwhile, blocks its border from the southward flow of non-Mexican refugees.

On the other hand, much modern malaise goes the way of affluence. “After a cascade of terrors on a life-and-death scale, nobody had the energy to be afraid of spiders….” A lack of drugs “sent addicts into a countrywide cold turkey…” Walking, tilling vegetables and “beating intruders with baseball bats had rendered Americans impressively fit. Sex-reassignment surgery roundly unaffordable, diagnoses of gender dysphoria were pointless…. No one had the money, time, or patience for pathology of any sort. It wasn’t that Americans had turned on oddity; they simply didn’t feel driven to fix it anymore.”

As for our most popularly presumed doomsday, Shriver all but ignores it. A passing reference comes in an especially disturbing home invasion. It’s committed by an unemployed “climate change modeler.” What Shriver does mention repeatedly, though, are shortages of fresh water. Environmental insight, as well as financial and political acumen, stand out in this story.

But The Mandibles’ greatest strength is characterization. Whether COVID-19 leads directly to collapse, whether society collapses suddenly or just continues to slide, there’s a human side to our downfall that maybe no one has captured like Shriver has. This frightening future is very much a story for the pandemic present.