Reflections on Vancouver, British Columbia and other topics, related or not

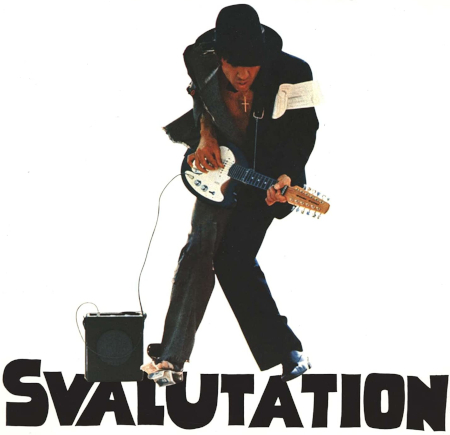

Salvation in Svalutation

Searching pop music for truth and transcendence,

and stuff

Greg Klein | October 10, 2022

Ridiculous as it was, rock and roll’s 1960s transition into something supposedly serious came close to wrecking a simple but lovable musical form. Damage was done not so much to the music but to the lyrics. Musically, rock branched off and blossomed in new ways. It was the lyrics that curled up and croaked.

Once rock scribes abandoned the teen themes so happily portrayed by songwriters ranging from Chuck Berry to the Beach Boys, the lyrics often became pompous, not to mention just plain bad. That’s obvious if you’ve ever wasted time reading some of them. Luckily you can rarely hear them clearly, thanks to the vagaries of rock “singing.”

Even so, the vocals sometimes suggest something verging on importance—even profundity, if rock stars are to be believed. That impression comes not from the actual words but their delivery. Dumb, trite or downright nonsensical as the lines might be, popsters sometimes fool fans into thinking the lyrics mean something.

Of course not everyone’s so susceptible. As Andrew Doyle said about PTSD flashbacks, “I once slipped and fell into a pile of horse excrement. So now I can’t listen to U2.”

But when the delivery works, more typical rock fans get to hear a “message” without having to understand it. And that makes Svalutation an ideal of rock expression.

The title itself is a nonsensical neologism. But it seems to convey something, seemingly. The rest of the lyrics are Italian, but they also seem to mean something—to those blessed with ignorance of the language.

Nevertheless, the song’s strongest exponents know Italian, even if they also think those words mean something. Of course a similar delusion afflicts purveyors of English-language rock and, when successful, just shows how a supremely self-confident character can inflict his fantasies on others.

Reinforcing that process are Svalutation’s multiple covers. A number of interpretations, while musically good rock, have pushed the illusion that “this song is about stuff.”

It started with Adriano Celentano’s original, a 1976 European hit referring to Italy’s economic tribulations. This TV spot shows Celentano dancing so excitedly that he seems ready to—get this—actually stand up.

Hank Shizzoe’s video followed the 2008 breakdown, strengthening his delivery with still images of financial chaos and economic collapse. All that furthers the lyrics’ claim to relevance, importance and urgency. And stuff.

In Francesco Gabbani’s 2012 version, Svalutation’s first verse becomes a political candidate’s pitch, only to be challenged by a rival singing the next verse. Disjointed scenes of sex and violence, a car crash and et cetera further the impression that, yes, this song is about stuff.

Then again, maybe the song does make sense in Italian. Maybe it’s only English-language pop lyrics that lack coherence. If that’s the case, Svalutation’s trivialized by Michelle Hànea.

Musically, it’s another good rocker but the band’s silly costume changes detract from any would-be message while the drummer’s brushwork almost gives the impression they’re syncing. (Surely not.)

Such playfulness risks a return to just plain fun. Could rock ever revert to such standards? No wonder pop fans now look elsewhere in their quest for whatever (and stuff). They’re even entranced by rapsters, whose grunting ghetto garbage makes less sense than Italian to a unilingual Anglo and cazzo! they sure do overuse that fucking F-word.

Of course gullibility and all-around mass stupidity can be expected from such thoroughly average people as pop fans. But what’s the Swedish Academy’s excuse?