Reflections on Vancouver, British Columbia and other topics, related or not

Lie in peace

and bury the facts

A new book exposes Canada’s mass graves hoax,

genocide smear and reconciliation chimera

Greg Klein | February 19, 2024

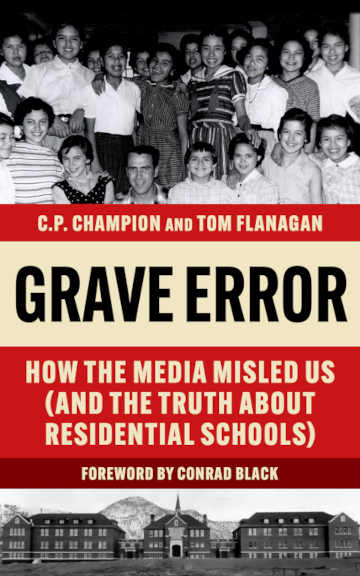

Editors C.P. Champion and Tom Flanagan wanted to publish

Grave Error before the Canadian government bans

dissenting information on the subject.

Powerful as this is—and it’s a damning rebuttal of all the bullshit behind Canada’s so-far worst outbreak of moral hysteria—the book’s understated. That caution begins with the subtitle: “How the media misled us.” Far more than media, the perp list features native leaders and native lawyers, along with native and non-native politicians and academics, among others.

They weren’t just misleading people either. They were (and are) lying outright, lying egregiously, lying again and again.

Public dissenters have been few but this book collects responses from some of the best-informed sources. Significantly most of them are retired, facing no employment risk. Contributor Frances Widdowson had already lost her tenured professorship at Mount Royal University. Another contributor stays anonymous.

Most chapters have appeared elsewhere, but none in mainstream outlets, which generally ignore this book too.

And the fact that, nearly three years after the first shock allegation, zero evidence has been found for 215 secret graves in Kamloops or any of the other locations where at least 2,600 supposedly murdered native children were supposedly dumped. The lie persists as a basis for “reconciliation,” an undefined, unattainable goal that combines chimera with extortion.

Either through incompetence or dishonesty, Sarah Beaulieu claims ground-

penetrating radar can locate possible graves. The “conflict anthropologist”

has won a tenure-track professorship at the University of the Fraser Valley.

Grave Error challenges not only the murdered and missing children hoax, but the further hoax that native schools somehow committed “genocide.” The term has been diluted to the point where rational minds would consider it meaningless, but this isn’t a rational era. “Genocide” still evokes horror and shame among whites, and self-pity and self-righteousness among natives. Yet genocide didn’t happen and residential schools didn’t cause “cultural genocide” (the end of the Stone Age).

Grave Error’s chapters were written separately by independent researchers and writers, so the compilation shows some overlap with a few contradictions. But repudiated in convincing detail are the two basic forms of evidence behind the unmarked graves/missing children hoax: ground-penetrating radar (GPR) and vague stories sometimes referred to as “tellings of Knowledge Keepers,” “knowings” or “truths.”

Shamelessly exploiting the emotional bullshit,

Justin Trudeau brings a teddy bear to this photo op.

Ground-penetrating radar cannot locate bodies, graves or possible graves. The “tellings,” “knowings” or “truths” don’t stand up to rational inquiry.

But you wouldn’t know that from the wildly unprofessional claims of a “conflict-anthropologist,” the emotional rhetoric of native spokespeople, the pusillanimous or opportunistic statements of non-native politicians, academics and lawyers, and the sensational to-hell-with-accuracy-or-rationality-or-even-three-digit-IQ media coverage. (See a timeline of events here.)

Of all the alleged locations across Canada, only four supposedly hidden gravesites have been excavated. No graves were found. Typical of most native bands, the Kamloops tribe vociferously opposes excavation. The band refuses to release the “conflict anthropologist’s” GPR report. The band also refuses to allow RCMP to investigate allegations of murdered children. Instead, we’re supposed to accept these eerie, rumour-like stories as unassailable.

At odds with the supposed “knowings” are school records that detail enrolment and attendance, as well as illnesses and deaths. Independent researcher Nina Green has documented vital info that Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission shrugged off. Nor has any evidence been provided to police about the murder allegations that popped up after the schools closed.

Other evidence, of long waiting lists from families trying to enrol their children, of bands protesting school closures, of positive accounts from former students, have been ignored or suppressed. As has evidence that the schools actually helped preserve native languages, contradicting a major tenet of the “cultural genocide” libel.

Chief among the hysteria-inducing malefactors has been the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, a heavily biased, manifestly dishonest process of racial opportunism. As Grave Error co-editor Tom Flanagan1 points out, all 94 TRC recommendations demand some kind of benefit for natives.

Truth and Reconciliation commissioner Murray Sinclair made wildly false

statements at the outset of the TRC hearings, then suppressed contrary

evidence. His dishonest, inflammatory report made 94 recommendations

for native benefits. This guy ranks among the top of Canada’s native elite.

The payouts have already been enormous and probably incalculable. They come from many different branches of different levels of government, and take the form of cash for individuals, bands and associations; land giveaways; subsidies and tax breaks for native businesses; free services; priority in medical care; job entitlements; sinecure entitlements; and a considerable degree of immunity from law, professional competence or even self-responsibility. Volumes could be written on the many ways natives have become Canada’s most powerful ethnic group. Yet “reconciliation” continues as the simplistic rationale for more, more, more.

The shakedown will continue permanently. That’s due to the “inter-generational” trauma of residential schools that had largely closed by the 1980s and shut down entirely in 1996. Even at the schools’ height, only a minority of native kids attended them. And now further “truths” are coming out about irreparable harm caused by day schools.

For ordinary Canadians, the propaganda has imposed a deep sense of shame. That too will be permanent, although occasionally sidelined by other outbreaks of moral hysteria like BLM/Antifa, “asylum seekers” or the teenage Swede. The current zealotry pushing kiddie gender-bending suggests that any kind of madness can sweep the mainstream.

That ongoing hysteria could have rated more attention in Grave Error, although there are references to moral panics. Some of the writers warn that genocide propaganda will further divide natives and non-natives. Maybe they miss the impact of relentlessly powerful ideological pressure that’s brainwashed some aspects of society and demoralized the rest.

Canada’s official missing native children propagandist Kimberly Murray

still pushes the fiction of 215 hidden graves at Kamloops. One theme of

her years-long National Gathering on Unmarked Burials calls for a ban

on contrary evidence and rational inquiry. She calls this censorship

“Affirming Indigenous Data Sovereignty and Community Control

over Knowledge and Information.”

Grave Error also pulls punches. There’s no mention of the virulent racism behind so many native spokespeople. Contributor Jonathan Kay2 blames the hysteria entirely on whitey. In doing so, he praises National Post columnist Terry Glavin for stating that, as Kay puts it, “the main reason the story was bungled was that journalists got it wrong, not that Indigenous leaders lied about what they believed.” (That claim was repeated by NP’s oft-inaccurate feature writer Tristin Hopper.) Belying that statement, as well as the book’s subtitle, are many references by other contributors to outlandish native statements.

Whether because of critical race theory or liberal condescension, Kay excuses natives with the weasel words “what they believed.” That implication of childish credulity, unintentional as it probably was, could move this topic further beyond the pale. Is this emotional bullshit—the “tellings of Knowledge Keepers,” “knowings” or “truths”—the best that can be expected from Canada’s aboriginal elite?

Certainly the entire “reconciliation” gambit hasn’t just cheapened public discourse, it’s helped build a native upper class of powerful, racist cretins. A few examples include Kimberly Murray and TRC commissioner Murray Sinclair. (Just a few more of many examples are here and here.) Among those filling out the ranks are manifestly unintelligent chiefs and a plethora of native lawyers who, interestingly, don’t actually practise law.

Residential schools were one of several failed attempts to prepare aboriginals for post-Stone Age life. Canada has since given up on integration, instead providing incalculable payouts and entitlements. While dissension is dangerous for non-natives, Canada’s most powerful ethnic group remains immune from responsibility—for their fellow natives, their families and themselves.

Again, can natives aspire to nothing better than the perpetual self-pity and self-righteousness of “inter-generational” trauma?

As for Canada’s non-native elite, the artificially created, unsolvable problem of “reconciliation,” the totalitarian overtones of criminalizing “denialism,” the climate of ideological zealotry and the strategy of divide-and-conquer can all benefit absolute power.

Could that be the purpose behind this madness?

Surveillance video catches an arsonist at Blessed Sacrament Church in Regina.

The February 9, 2024, fire marks the hundredth church attack recorded by True

North news since the May 2021 “mass graves” hoax began in Kamloops.

Some of the lies refuted in Grave Error

While residential schools were in operation, most native children attended them.

They did so by force.

Thousands of those students went missing and have never been found.

Those missing children are buried in unmarked graves on or near school or church properties.

Many of the missing children were murdered by school staff following physical and sexual abuse.

Ground-penetrating radar can locate graves.

Ground-penetrating radar has located many of the children’s bodies. Many more will be found as government-funded searches continue.

Residential schools destroyed native languages and culture.

Residential schools have traumatized all natives.

Although most residential schools had closed by the 1980s and the last in 1996, residential schools will continue to traumatize all natives in perpetuity.

Related:

A timeline of Canada’s genocide hysteria

1Among his 1990s services to Canada’s Reform Party, Flanagan combed party membership lists for names of suspected “racists,” whom he recommended for expulsion. Would Flanagan have passed someone who participated in a book like Grave Error?

BTW his 1995 book Waiting for the Wave: The Reform Party and the Conservative Movement has some useful chapters for anyone interested in the Preston Manning disappointment. Flanagan has also written other books on Canadian native issues.

2 Not surprising to anyone who’s read Kay’s MSM-wannabe writing at Quillette, he proclaims his PC cred with this prediction in Grave Error:

“There is surely no shortage of real evidence of past atrocities waiting to be found by researchers. It seems inevitable that some day in the future, actual bodies will be brought to the surface—genuine, uncontestable evidence of a real historical atrocity that formerly had been unknown or obscure.”

A back-cover blurb by Kay’s mother, National Post columnist Barbara Kay, tarnishes Grave Error. Suggesting that she’s a Jewish bigot are at least two NP articles she wrote praising a racist novel called The Siege of Tel Aviv. (Would she have passed Flanagan’s 1990s purges?)