Reflections on Vancouver, British Columbia and other topics, related or not

Lionel “Mitch” Mitchell

An early Vancouver jazz talent

The tenor saxophonist played with Count Basie, according to an April 10, 1964, jazz column in the Vancouver Province; with Jimmie Lunceford, according to a July 19, 1952, Vancouver Sun feature entitled Negroes Live Next Door; and/or with Duke Ellington, according to what I remember from my parents, who were friends of Mitch.

He was possibly Vancouver’s first homegrown jazz musician of significant stature, except he likely wasn’t quite homegrown. He spent at least part of his childhood on the Sunshine Coast.

The two black kids outside Vancouver Bay School on the Sunshine Coast

are Lionel Mitchell and his brother Leslie, maybe positioned right and

left. (Photo: Sunshine Coast Museum & Archives)

Nevertheless the childhood was musical. Here’s an excerpt from Mark Miller’s definitive 1997 book Such Melodious Racket: The Lost History of Jazz in Canada 1914-1949:

There were four brothers in the Mitchell family, Stan—the eldest—Elliott, Lionel and Les. Their father, Greenwood Mitchell, a logging engineer, had arrived in Vancouver as a travelling musician from Montgomery, Alabama, via Chicago; mindful of his sons’ limited prospects in British Columbia outside of logging and, of course, the railroad, he encouraged their interest in music, providing instruments and some semblance of instruction.

With Coleman Hawkins as a strong early influence, Lionel stood out among his siblings. As Les told Miller:

Either you’re a musician or not, and he was. It seemed like it was no effort for him to sit down and practise for hours. He couldn’t get enough of it.

Mitch holds a clarinet in this late-1930s Edmonton scene with Tiger Ace

Bailey and his Knights of Swing. The cover photo of Miller’s book, also

reproduced inside, comes from the same photo session in which

some band members switched instruments for different shots.

After gigging around Vancouver and a few other B.C. locations, Miller relates, Mitch joined Ollie Wagner’s Knights of Harlem in 1935 at age 18. He worked in Seattle, Portland and Edmonton by 1940, when he fronted his own band at Vancouver’s Log Cabin Inn, a black cabaret that the following year advertised a “colored floor show” with Southern fried chicken and hot biscuits included in the $1.05 cover charge.

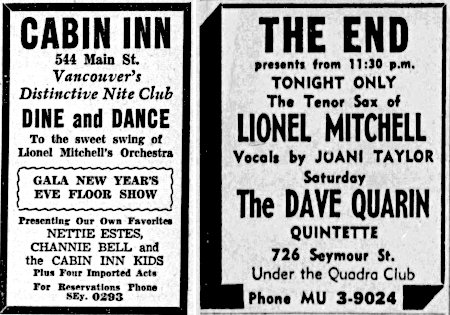

A couple of newspaper ads from 1940 and 1964.

The 544 Main Street address (later the New Delhi Cabaret) placed the club near Hogan’s Alley, a now-demolished neighbourhood that hosted Vancouver’s largest concentration of black residents and some notorious nightspots, spawning anecdotes that must be heard to be disbelieved.

But some credible accounts have survived the mythology. Log Cabin Inn manager Buddy White “was one of the baddest badasses in town,” writes Vancouver Postmedia reporter John Mackie. “In 1933 he was sentenced to 15 months in jail for attacking a man who needed 75 stitches to close his wounds. In 1941 he was sentenced to three months in jail for having a gun at the Log Cabin Inn.”

Mitch might not have been out of place. In 1941 he got a two-month sentence for assault. As the Vancouver Province reported, “A waiter in [the] Main Hotel beer parlor testified that Mitchell had pulled a razor from his pocket when he had warned him to be quieter.”

Circa 1942 Mitch joined the U.S. Army, serving as a band musician, Miller notes. (Wayde Compton has attributed the southward migration of Vancouver blacks to a small local black population that provided few eligible same-race spouses at a time when society discouraged cross-racial relationships. However Mitch did marry at age 20 to a Vancouver girl also of black American parentage.) Mitch’s big-name big band touring must have followed the war.

Back in Vancouver Mitch led or worked in small combos, sometimes with pianist/organist Mike Taylor, a Californian transplant who was a mainstay of Vancouver jazz up to about the early ’80s.

Besides Miller’s account, Mitch got brief recognition in Marian Jago’s book Live at the Cellar and was apparently remembered by those familiar with Hogan’s Alley.

Mitch died in December 1975, with the cause possibly related to a brain tumour. His last employment, as far as I know, was as a West End apartment building manager.

I’m not aware of recordings by any of the Mitchells. It was by no means unusual that outstanding musicians of the period weren’t recorded.

So ended a remarkable life, recounted here in only the briefest outline. Mitch was a (formally) unschooled musician of considerable achievement who carried on a black American tradition in a largely white Canadian city. Yet he ended up in obscurity as popular music that had often been jazz-related turned away from sophisticated melody and harmony, away from instruments other than guitar, and away from music itself to replace it with image, expressed mostly through appearance, demeanour and behaviour.

Miller’s book provides much more info about Mitch. Both Miller’s and Jago’s books offer highly informative and readable accounts of Canadian musical and social history.