Reflections on Vancouver, British Columbia and other topics, related or not

Just off Broadway

Musicians co-operated on stage and off

to give Vancouver jazz a lasting legacy

Greg Klein | July 21, 2019

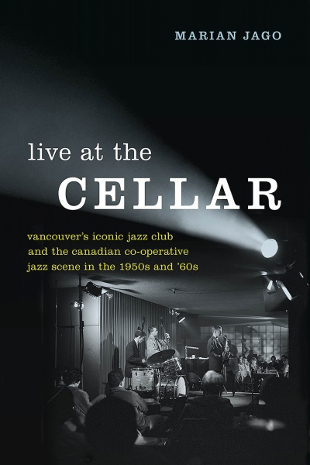

An unusual combination of musical and historical chops makes Marian Jago unusually qualified to write this. Live at the Cellar documents how a group of jazz musicians and enthusiasts formed a co-op that made Vancouver musical and social history.

A somewhat weird side street address (2514 Watson Street was also 222 East Broadway) added a nice touch to the venue’s repute as an outlet for new music and a beat-era hangout that lasted a decade up to 1965. Here, an upcoming generation of musicians from Vancouver and across Canada provided themselves with gigs as well as listening and playing opportunities with more accomplished American talent. Canadians associated with the Cellar went on to achieve considerable stature in this country and in some cases internationally.

One example was Terry Clarke. As a 15-year-old protege of legendary drum instructor Jim Blackley, he heard Charles Mingus for the first time at the Cellar. It proved to be an epiphany:

And that first, that evening, completely changed my life. I was so terrified, and blown away. My head just blew off. And I remember sitting there for the hour break that they took, just thinking … my whole life flashed before me and what music was all about, and why did I understand it. What blew me away is that what Jim Blackley and I had been talking about, as far as rhythm sections and rhythms and three-beat rhythms and vamps and riffs and things […] And I said, “This is exactly what we had been talking about. Now, I get it.” The light bulb had gone on. “I get it,” you know.

Jago also relates one aspect of Vancouver’s might-have-been potential as a cultural centre. There was a time, before becoming the precinct of rich Chinese, narcissistic junkies and pompous flakes, when the city could attract talent. There was talk, for example, that the Vancouver Symphony would gain international renown with exceptional musicians willing to take a pay cut just to live here. Boosterish artsy types touted the city as a natural magnet for other artsy types. In the Cellar’s case, the club gained a rep in California for allowing musicians to play their own music unimpeded by commercial constraints. Shortly before becoming famous, Ornette Coleman tearfully thanked Cellar staff for just that reason. Some well-established Americans stayed with Vancouver musicians and returned to visit the city. At least a few moved here specifically because of the Cellar.

Yet the Cellar’s Canadian contingent was mostly white. Noting the very small local black population of the time, one source said they seemed to prefer R&B. Mentioned briefly, however, is Vancouver’s Lionel Mitchell, described by sax player Gavin Walker as “a very fine big-sounding, no-bullshit tenor player that a lot of people liked. And he was an infrequent kind of sitter-in.”

I understand that Mitch (he was a friend of my parents) toured with Jimmie Lunceford and Duke Ellington. He must have been Vancouver’s first homegrown jazz musician to achieve impressive artistic stature and merits considerable attention in Mark Miller’s Such Melodious Racket, a great history of Canadian jazz that has interesting sections on Vancouver.

The Harlem Nocturne, an anomalous black club that operated on east Hastings in the ’50s and ’60s, was run by an Edmonton black, trombonist/band leader Ernie King. This isn’t noted by Jago but he’s another example of the influence on Vancouver music of blacks from Alberta, a province that at least by the 1990s seemed bereft of homegrown blacks. Legend has it that Vancouver’s once-vibrant R&B scene got started by a band called the Calgary Shades, an otherwise black group that included Cheech’s future partner Tommy Chong.

(If “Shades” was racially risqué, a later version of this band went further by renaming themselves Four Niggers and a Chink, an absolutely appalling appellation for a combo which eventually became Bobby Taylor and the Vancouvers and which might have been down to only one Albertan who—let’s be precise here—was the chink, not one of the niggers.)

King maintained that racism prevented him from getting a liquor licence. Interestingly and not mentioned by Jago, Ronnie’s Riverqueen, a Davie Street club that booked big jazz names and hosted after-hours jams during the ’60s and ’70s, couldn’t get a liquor licence either. Race might have been a factor for Ron Small, co-owner with his wife Shirley.

Jago states that King also attributed racism to his lack of downtown nightclub work. But she quotes Mike Taylor, a black American pianist and long-time fixture of Vancouver jazz, saying that King would have had to “practise more” to qualify.

Jago and her sources discuss Vancouver race relations from a number of perspectives, often focusing on whether blacks were deliberately shut out of the more lucrative but intensely competitive downtown gigs. Chuck Logan, a black drummer from California who was involved in the Cellar early on, had this to say:

I found that it was the French [?], the East Indian and the Native [who] were worse off than I was. But there was still the unsurety of the black, because of Fort Lewis down in Washington, and the Seabee base in Bremerton. They used to come up here and basically, there was nothing but white girls, and the blacks really didn’t know how to handle that situation. You know … which would create some problems in due time … My colour came into it on occasion, but not much.

Adding more context, the book discusses other Vancouver venues, from the 1910s-to-’20s bars, clubs and theatres along Hastings and Pender where Freddie Keppard and Jelly Roll Morton played, to the swing era clubs and dance halls of downtown, Chinatown, the West End and west side, to the beatnik coffee houses and clubs that popped up later. Some of the latter, especially the Flat Five, provided competition that probably hastened the Cellar’s end. Yet the competition had an even shorter lifespan.

The Smalls reopened the club in 1970, after the Riverqueen succumbed to financial difficulties. No longer a co-op and now called the Old (or Olde) Cellar, it was possibly an off-and-on venue. Around that time I heard performances by Herbie Hancock, Almeta Speaks (who had a strong local following) and a return engagement with Ornette Coleman. The Smalls’ efforts lasted maybe a year and a half. The building got demolished in 2014, not before some resident rock-lifestyle cretins torched parts of the structure.

The book’s foreword by Don Thompson lists several club closures across the U.S. and Canada from the mid-’60s to mid-’70s. The multi-instrumentalist blamed colour TV and the profusion of new channels. No one in the book mentions the period’s racial violence that made American downtowns dangerous for non-blacks. Nor does anyone mention musician arrogance, which could include showing up wayyyy late, then taking really long breaks, a problem acknowledged at the time by Downbeat.

But a number of the book’s sources blame rock. Jago attributes the Cellar’s demise at least in part “to the widespread cultural shifts of the 1960s that tilted countercultural activity away from jazz and jazz-based expression toward other forms of popular culture.”

In other words, the pseuds took their business elsewhere. That might have blessed jazz with an audience that likes the music solely for the music’s sake, but of course it’s a much smaller audience. Eventually government stepped in with a loose definition of Canadian culture. Even though Canada has created no distinctly Canadian jazz, tax-funded grants and subsidies now help support musicians, concerts and festivals. Jazz training, meanwhile, more commonly takes place on college campuses than in film noir settings, further diminishing the music’s aura.

That might be good if the aura attracts people for non-musical reasons. Still, you can’t help wonder if there’s some excitement and mystery to the music that’s best experienced in gritty surroundings. Would such an epiphany have struck Terry Clarke in a university program?