Reflections on Vancouver, British Columbia and other topics, related or not

Survival stories

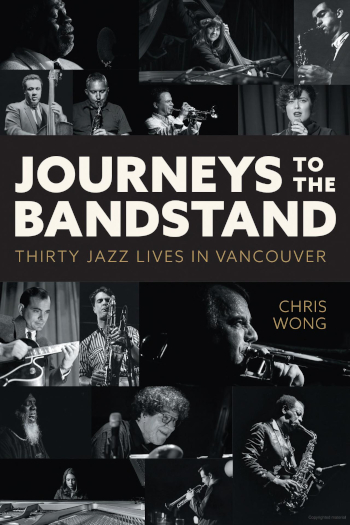

Chris Wong’s jazz biographies relate

Vancouver perseverance as well as talent

Greg Klein | December 29, 2025

Over a decade in making and backed by considerable research, extensive interviews, a great deal of listening and genuine insight, this book demonstrates commitment equal to that of the musicians themselves. Not intended as a comprehensive history, the work documents 30 sometimes-interrelated subjects involved in this city’s precarious jazz scene. Chris Wong explores a bigger story yet in the human side, who these individuals are and what motivates them.

He begins with aficionados who eventually formed a musicians’ co-op, an historic development more thoroughly discussed in Marian Jago’s 2018 book Live at the Cellar: Vancouver’s Iconic Jazz Club and the Canadian Co-operative Jazz Scene in the 1950s and ’60s.

That was a time when local musicians had little to draw on, other than a limited supply of records and Bob Smith’s radio show, to explore the fascinating new music happening south of the border. Wong writes about people like trumpeter John Dawe, for example, learning and playing bop in “real time” as the music developed. The author manages to get near-recluse Dave Quarin talking. The Strathcona guy played sax with Ernie King’s mixed-race touring band before, like trumpeter Bobby Hales, becoming a Cellar pioneer while also a Downtowner, one of the exceptionally sharp sight-readers who backed big names in clubs like Isy’s and the Cave.

One of the Cellar co-op’s imports was

Don Cherry on trumpet, seen here with club regulars

Chuck Logan on drums and Dave Quarin on alto in 1957.

P.J. Perry, who came to be considered Canada’s top alto player, surprised Cellar vets from an early age. He got in some enviable teenage experience playing the Smilin’ Buddha in Chinatown and the New Delhi in Hogan’s Alley while still in high school bands at Como Lake and (ffffffwhat!?!) Gladstone before moving uptown to Downtowner jobs backing the likes of Lena Horne, Peggy Lee and Ella Fitzgerald.

American ex-pat Ron Small got started in a doo-wop group that made a 1958 Ed Sullivan appearance. His musical and personal odyssey brought him to Vancouver where he sang and MCd at clubs before running the legendary Riverqueen, hosting bands like Cannonball Adderley and Bobby Hutcherson with Harold Land. A non-jazz event brought on four years of legal turmoil for staging a supposedly obscene play. Some vicissitudes later, Small sang gospel with the Sojourners, capping a career that, among other things, shows the interrelation of different modes of black American music.

More recent names include pianist Tilden Webb, bass player Jodi Proznick and drummer Jesse Cahill, three relatively young talents working together in mutual admiration, sometimes backing big names from the U.S. Profiling musicians in the roughly chronological order of their careers, Wong takes us up to singer Natasha D’Agostino, her life cut short in a 2019 car crash at age 26.

There’s much to appreciate in this book but above all it’s a tribute to Cory Weeds. Vancouver’s recipient of the amended James Brown title, the Hardest Working Man in Jazz Business, has long been tireless in presenting and recording local musicians, all the while developing his own sax playing. Many of Wong’s subjects were part of the Weeds orbit, which even drew musicians from other solar systems. Without Weeds, this book—not to mention the Vancouver scene—would have been much smaller.

Michael Glynn and Cory Weeds recording for the Cellar Live label.

A one-man force by his mid-20s, he opened his Cellar club in 2000 at the opposite end of Broadway from the now-closed co-op. Drawing on personal loans, bank loans, donations, investments, some staff volunteers and tax funding, Weeds made his club the jazz venue in Vancouver.

Unintentionally reflecting a weak market, the club seated a maximum 67 people before expanding to a still-modest capacity of 90. Some nights would see full houses, others drew very few listeners.

His Cellar Live record label debuted in 2002. Within seven years Weeds released 50 albums, some by well-known Americans but most by local musicians.

The club became known for presenting American names backed by Vancouverites. That led to Weeds’ friendships with much older musicians like sax player David Fathead Newman, pianist Harold Mabern and tenor legend George Coleman. After booking Lonnie Smith, Weeds and his band Crash toured with the septuagenarian B3 wizard.

Peer-to-peer these relationships weren’t. Given the roughly three-decade age difference and completely divergent backgrounds, Wong says, “it wouldn’t have been surprising if the elders had kept some distance with Weeds. But they were genuinely drawn to each other.”

Nice, but why not reach out to musicians of a more contemporary age or, at least, not so antiquated? Obvious as it is, the question’s unasked.

Still, the opportunity to back such talent, even if past its prime, helped local musicians mature. And as a sax player himself, Weeds says the experience of running the club, of hearing and participating in the performances meant “I actually became a real musician.”

Years of financial struggle, however, drove him to shut down the Cellar in 2014. The record label continued, as did Weeds’ booking and playing gigs at other venues. Wong considers the ever-irrepressible force as “a virtuoso of getting shit done and making things happen.”

A veteran of both Cellars and a Canadian great: On reaching 80

P.J. Perry said, “It’s taken me all my life to experience the freedom

to spontaneously create music and play what I hear in my head.”

(Photo: Steve Mynett)

Several of Wong’s chapters cover the visiting Americans, even though they’re hardly products of this city.

Brief appearances by Charles Mingus and Ornette Coleman at the original Cellar were considered seminal events by many Vancouverites. (Read about drummer Terry Clarke’s Mingus epiphany.) As for the other Americans, their relevance to this book mostly comes from interaction with locals.

That context often presents the book’s recurring theme of self-doubt. Youngish middle class college- and university-trained Canadian white and Asian musicians were often intimidated by the prospect of backing much older, more accomplished veterans of the black American jazz milieu.

The interplay could be awkward. During a 2004 Cellar performance, sax near-giant Frank Morgan shouted angrily at two Vancouver musicians right on stage. (Weeds, on the other hand, insisted the ensemble played “some of the most beautiful music that had ever been made at the club.”)

At a chance meeting between Weeds and Lou Donaldson in New York, the 87-year-old alto player remarked on Cellar Live, the label that pumped out 50 local albums in just seven years: “Those records you’re putting out in Vancouver, that’s some sad shit.”

But Wong relates compliments from the likes of Newman, George Coleman, drummer Roy McCurdy and others. After a 2006 Cellar performance backed by Ross Taggart on piano along with Proznick and Cahill, Coleman said, “Vancouver, you’re in pretty good shape. The guys, they can play, and the girls too.”

Wong doesn’t consider Journeys the alpha and omega of Vancouver jazz bios. Just the same, the book would have been richer with a chapter on Jelly Roll Morton, whose Vancouver stay lasted much longer than those of most Americans profiled by Wong. Difficult to research maybe, but the topic might also reveal new info on early jazz in Vancouver and the Hastings-and-Main entertainment district where people like Ada Bricktop Smith, Freddie Keppard and Charlie Chaplin performed. (Jago’s Live at the Cellar covers some of this as does another excellent Canadian jazz history, Mark Miller’s Such Melodious Racket, but “historian” Aaron Chapman missed it entirely in his book about Vancouver night life.)

Another talent deserving attention was Lionel Mitchell. The tenor player was possibly B.C.’s first jazz musician of significant stature and, maybe relevant, one of B.C.’s few native blacks to play jazz.

Scottish ex-pat Jim Blackley was a drum instructor/mentor/inspiration who apparently failed to break into Vancouver’s gigging network, presumably the Downtowners. Yet his protegés keep popping up in Wong’s book.

Also conspicuously absent is American ex-pat drummer Steve Ellington, an especially surprising jazz migrant for his breadth of experience and talent.

But the most serious omission might be another ex-pat, keyboards player Mike Taylor. He’s mentioned only in passing although he spent more than 20 years as a mainstay of Vancouver jazz, ran or partnered in a number of venues, encouraged all kinds of younger musicians (with whom he could show remarkable patience), and played with many of the local standouts, including Mitchell and Ellington (Steve, not his grand-uncle).

It might be noted too that this big, fat book could have lost considerable flab by shedding unnecessary detail and over-explanation. Wong will decry what he calls a “weightist and offensive description,” but even the Mingus chapter is rotund.

A Cellar Live performance of Sticks: Roy McCurdy drums, Thomas Marriott trumpet,

Cory Weeds tenor, Michael Glynn bass, Marc Seales piano.

But back to Weeds. If this guy couldn’t give jazz greater prominence in this town, who could? Even the profusion of jazz programs at the secondary, college and university levels fails to boost audience turnouts. Apparently few jazz students patronized the Cellar’s student discount promos. That indifference seems odd, very odd, to someone once familiar with the 4:00-to-5:30 a.m. Riverqueen-to-home teenage trek through the West End, downtown, Chinatown, Strathcona and into eastern East Van, during which time memories of music gave way to fear of getting jumped.

As the book reports, some jazz students aren’t even interested in jazz. In some classes, they’re the majority.

That can only heighten uncertainty about the future of jazz—if in fact jazz still exists. The music hasn’t had a clear forward focus for many years. Much of the local music discussed by Wong consists of tributes and re-interpretations. They’ve always been a welcome feature of jazz, but not to the exclusion of a new direction. Meanwhile jazz dissipates into multi-influenced musical menageries. Its support, here in Canada anyway, relies largely on tax money.

So has jazz played itself out and, if so, how and why? That’s another discussion for another book, maybe with accompanying CDs.

What Wong has accomplished, though, is tremendous. He describes music with skill and insight, he nails down details clearly, and he strives valiantly to understand the people, their motivation to work and their inspiration to play. His book well serves this somewhat neglected art in a rather indifferent town.